Staying Fit

As autumn comes around, so do the placards and public service announcements alerting us to get our flu shots, update our COVID-19 vaccines and generally get on top of the inoculations we need as we get older.

But after three years of culture wars, dogmatic dogfights and scientific stops and starts, the idea of getting that next shot seems unusually fraught — especially when anti-vaccine celebrities are in the thick of today’s political debates.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

New research has provided yet one more reason why staying on top of your vaccinations makes sense: They might decrease the risk of age-related cognitive decline.

“Vaccination is the right thing to do to protect yourself from flu and other infections,” says Paul E. Schulz, M.D., professor of neurology and director of the Neurocognitive Disorders Center at the McGovern Medical School at UTHealth Houston. “Now there is also the potential fringe benefit of vaccination, which is reducing the risk of Alzheimer’s.”

In recent years, studies have found that those who get vaccinated for the flu and other infectious diseases appear less likely than their unvaccinated counterparts to get dementia — although it’s unclear what happens in the brain to cause this. One theory some experts have is that infection plays a role in developing Alzheimer’s disease and that vaccinations may help stave off these infections.

Others, like Schulz, say it’s possible that vaccination may reduce an immune system function that attacks amyloid plaque (a protein found in abnormally high levels in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients) as an invader, causing chronic brain inflammation and the death of nearby cells.

“The problem in Alzheimer’s is that the immune system keeps trying to get rid of the plaque, and it can’t,” Schulz explains. “The plaque sits there for 10 years, and the immune system keeps throwing poisons at it all that time and is killing brain cells in the process.”

More From AARP

Are COVID-19 Vaccines Still Free?

Feds no longer paying the bill

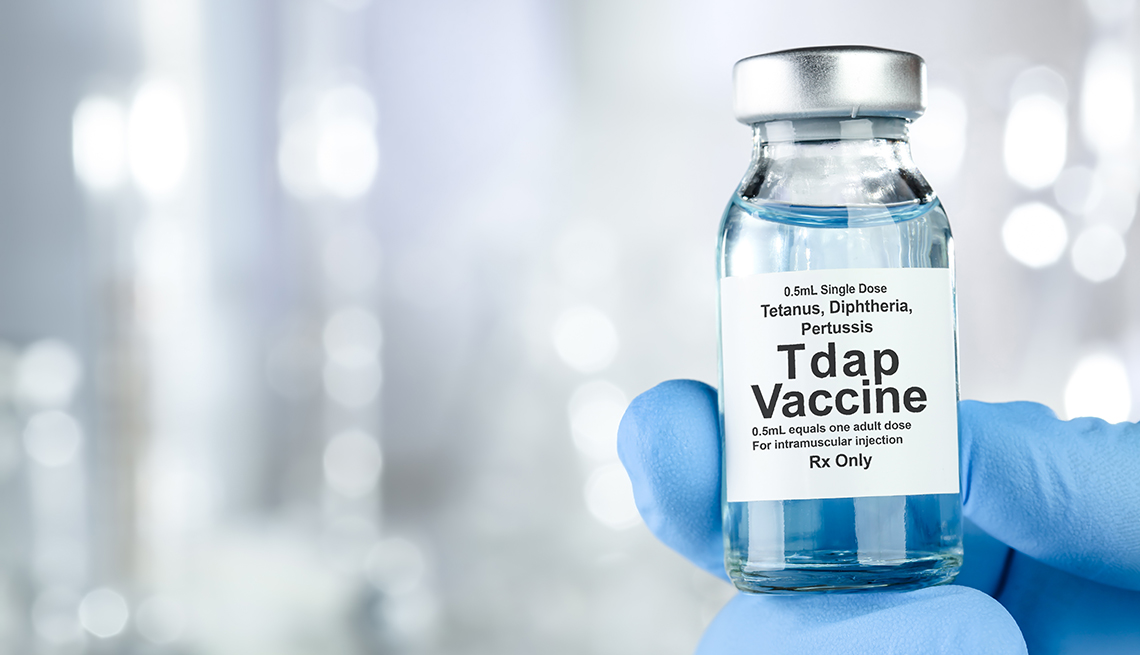

What to Know About the Tdap Vaccine

Details on what the shot does — and when you need itTurning 50? Go Get A Shingles Vaccine

It's extremely effective, preventing a super-unpleasant infection. So why don't more adults get it?